Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis: Medications That Scar the Lungs

Jan, 12 2026

Jan, 12 2026

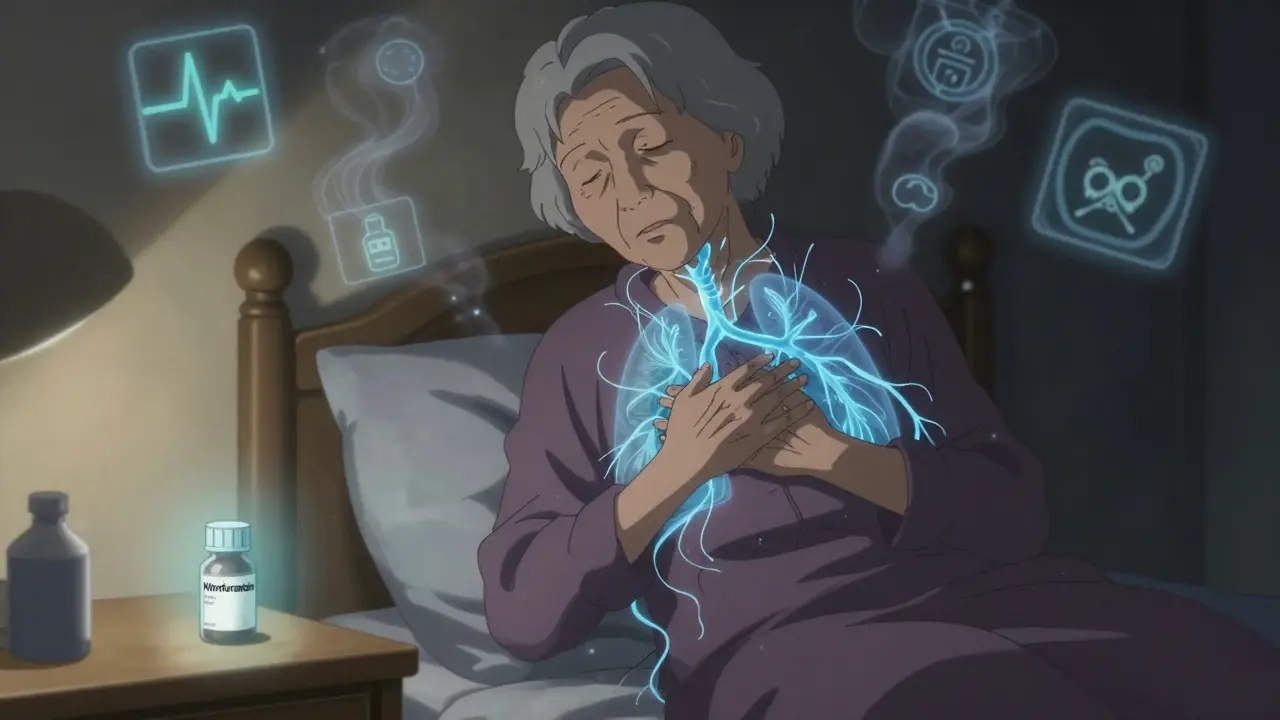

Imagine taking a pill every day to manage your arthritis, heart rhythm, or infection - only to find out months later that it’s slowly scarring your lungs. This isn’t a rare nightmare. It’s happening to real people, often without warning. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF) is a hidden side effect of common medications that causes irreversible lung damage. And most patients don’t realize what’s happening until it’s too late.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis is when certain medications trigger inflammation and scarring in the delicate walls of your lungs’ air sacs. This scarring, called fibrosis, makes the lungs stiff and thick. Oxygen can’t move through easily. Breathing becomes harder - not just when you run, but when you walk to the kitchen or get dressed.

Unlike normal aging or smoking-related lung damage, DIPF is caused by a direct reaction to a drug. It doesn’t happen to everyone. In fact, most people take these medications without issue. But for some, the body’s immune system overreacts. Collagen builds up where it shouldn’t. The lungs turn from spongy to stiff, like old rubber.

Doctors call it an idiosyncratic reaction - meaning it’s unpredictable. One 72-year-old woman on nitrofurantoin for a urinary tract infection might develop fibrosis after 8 months. Another person on the same drug for 10 years never has a problem. There’s no clear reason why.

Medications That Can Scar Your Lungs

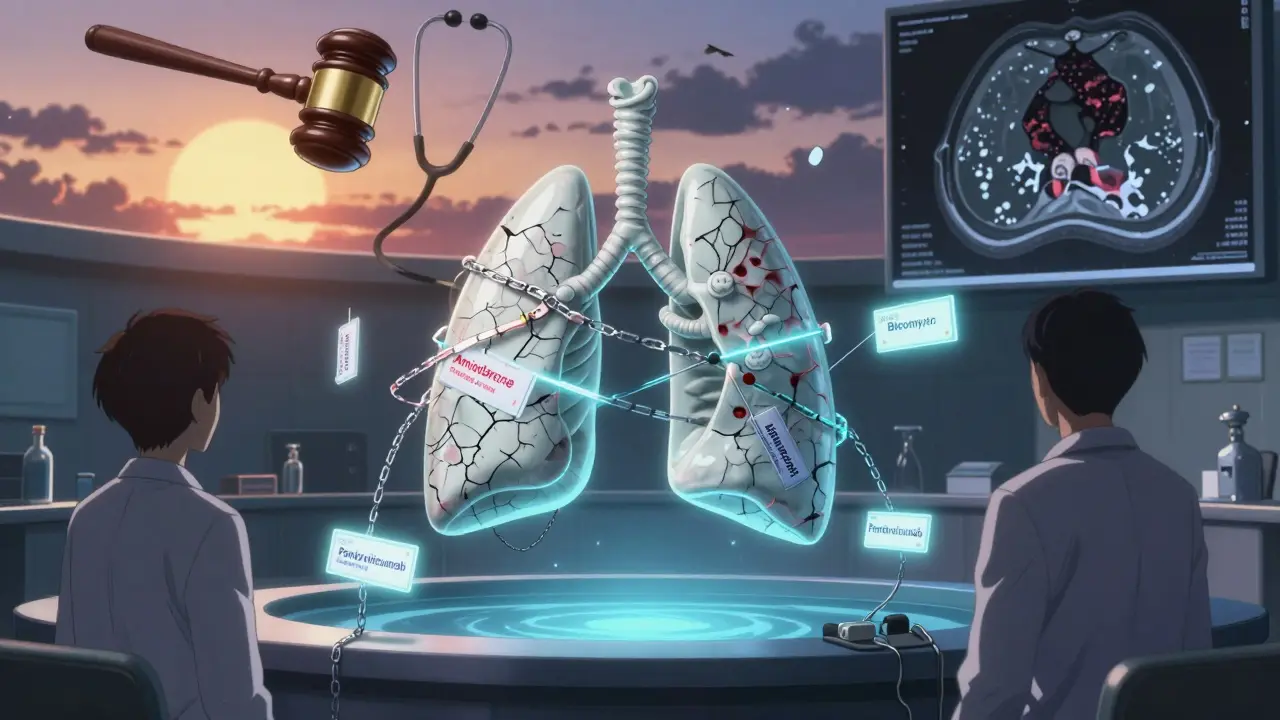

More than 50 medications have been linked to pulmonary fibrosis. But only a handful cause most cases. Here are the top offenders, based on real-world data from New Zealand’s pharmacovigilance system (2014-2024) and clinical studies:

- Nitrofurantoin - Used for urinary tract infections. Often prescribed long-term for prevention. Accounts for 47 cases in a 10-year database. Most common in older adults. Symptoms can appear after 6 months to 10 years.

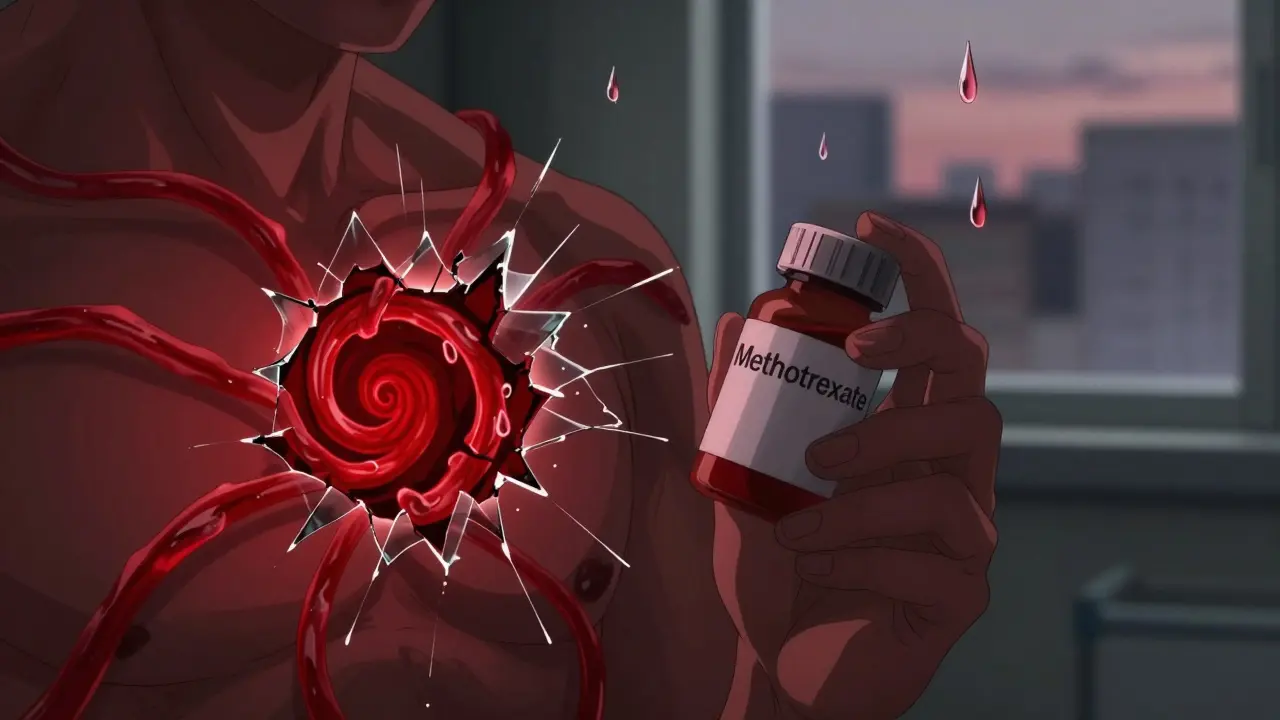

- Methotrexate - A common treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Causes lung damage in 1-7% of users. Often hits fast - acute pneumonitis can develop in weeks. 45 cases reported in New Zealand.

- Amiodarone - Used for irregular heartbeats. Up to 7% of long-term users develop fibrosis. Risk rises after cumulative doses over 400 grams. Takes 6-12 months to show up. 39 cases recorded.

- Bleomycin - A chemotherapy drug. Up to 20% of patients get lung toxicity. Often happens after just a few doses. High risk, fast progression.

- Cyclophosphamide - Another chemo drug. Around 3-5% of users develop fibrosis. Often combined with other drugs, making it harder to spot.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors - Newer cancer drugs like pembrolizumab and nivolumab. First approved in 2011. Now among the fastest-growing causes of DIPF. The immune system, unleashed to fight cancer, ends up attacking the lungs.

- Penicillamine and gold compounds - Older arthritis treatments, still used in some cases. Known for lung damage since the 1950s.

Here’s what the numbers tell us: Nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, and amiodarone together made up 42.8% of all medication-related lung scarring cases in New Zealand over a 10-year period. And 30 people died from these reactions.

How Do You Know If It’s Happening to You?

The symptoms are quiet at first. Most people ignore them.

- A dry cough that won’t go away - not from a cold, not from allergies.

- Shortness of breath during normal activities - climbing stairs, carrying groceries.

- Fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest.

- Unexplained fever or joint pain.

According to Action Pulmonary Fibrosis, 78% of patients report worsening breathlessness. 65% have a chronic cough. 32% get fevers or joint pain.

Here’s the problem: these symptoms look like aging, asthma, or heart failure. Many patients wait months before seeing a doctor. One Reddit user shared: “I thought I was just getting out of shape. By the time I got diagnosed, I was on oxygen at night.”

Studies show the average delay in diagnosis is 8.2 weeks. By then, scarring may already be advanced.

Why Is It So Hard to Diagnose?

There’s no single test for drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. No blood marker. No unique pattern on a CT scan.

Doctors have to rule out everything else - infections, autoimmune diseases, asbestos exposure, sarcoidosis. That’s why your medication history matters more than anything.

“If you don’t ask about the drugs someone is taking, you’ll miss it,” says Dr. TE King, co-author of the leading textbook on interstitial lung disease. “It’s not about what the scan shows. It’s about what’s in the pill bottle.”

Even radiologists can’t always tell the difference between DIPF and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) - the kind that happens for no known reason. The only way to be sure is to stop the suspected drug and watch what happens.

What Happens If You Keep Taking the Drug?

Continuing the medication means more scarring. And scarring is permanent.

Amiodarone can keep damaging your lungs for months after you stop. Methotrexate can trigger a rapid, deadly form of lung inflammation. Bleomycin can cause irreversible damage after just one or two doses.

One study found that patients who kept taking nitrofurantoin after symptoms started had a 60% higher risk of needing long-term oxygen or dying from lung failure.

There’s no magic pill to reverse fibrosis. Once the scar tissue forms, it doesn’t go away. That’s why stopping the drug early is the only real treatment.

Can It Be Treated?

Yes - if caught early.

The first and most important step: stop the drug. That’s it. For many, that’s enough.

According to Action Pulmonary Fibrosis, 89% of patients improve within 3 months of stopping the offending medication. Some even regain most of their lung function.

If symptoms are severe, doctors add corticosteroids - usually prednisone. A typical dose is 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight daily, then slowly tapered over 3-6 months. It reduces inflammation but doesn’t undo scar tissue.

Oxygen therapy is used if blood oxygen drops below 88%. Pulmonary rehab helps with breathing techniques and stamina.

But here’s the hard truth: 15-25% of patients never fully recover. They’re left with permanent lung damage. Some need a transplant.

Who’s at Risk?

It’s not just older people - though most cases are in those over 60. Risk factors include:

- Long-term use of high-risk drugs (especially nitrofurantoin for UTI prevention)

- Higher cumulative doses (amiodarone over 400 grams)

- Pre-existing lung conditions like COPD

- History of radiation therapy to the chest

- Genetic factors - we’re still learning which ones

And here’s something most don’t know: primary care doctors often don’t screen for it. A 2022 survey found only 58% of GPs routinely ask patients on high-risk drugs about breathing symptoms.

How to Protect Yourself

You don’t have to avoid these medications. Many are life-saving. But you need to be smart.

- Ask your doctor: “Could this drug cause lung damage?” If they say no, ask for the evidence.

- Know your symptoms. Dry cough? Shortness of breath? Don’t brush it off. Write them down.

- Get a baseline lung test. If you’re starting amiodarone, methotrexate, or nitrofurantoin long-term, ask for a pulmonary function test (PFT) before you begin. Repeat it every 6 months.

- Report symptoms immediately. Don’t wait. Tell your doctor - and insist on a chest CT if needed.

- Keep a medication list. Include doses and start dates. Bring it to every appointment.

Regulators like New Zealand’s Medsafe now warn doctors: “Inform patients about this risk before prescribing.” That’s progress. But it’s still not standard everywhere.

The Bigger Picture

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis is rising. Reported cases have increased by 23.7% over the last decade. Why? More drugs. More people on long-term meds. Better reporting.

New cancer drugs, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors, are a growing concern. These drugs are powerful - but they can turn your immune system against your lungs. Doctors are still learning how to predict who’s at risk.

Research is underway to find genetic markers that might predict who’s vulnerable. Until then, vigilance is your best defense.

Every drug has risks. But for DIPF, the risk is silent. It doesn’t show up on a blood test. It doesn’t hurt at first. It just steals your breath, one step at a time.

If you’re on one of these medications - even if you feel fine - pay attention. Your lungs can’t tell you they’re hurting. You have to listen for them.

Can you get pulmonary fibrosis from short-term antibiotic use?

Yes, but it’s rare. Nitrofurantoin is the main offender, and it usually takes months or years of use. Most people take antibiotics for 5-10 days and never have an issue. The risk comes from long-term, daily use - like taking nitrofurantoin every night for years to prevent UTIs.

Is pulmonary fibrosis from drugs the same as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis?

The scarring looks the same on a scan, but the cause is different. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has no known cause. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF) is caused by a medication. The key difference? DIPF can improve - even reverse - if you stop the drug early. IPF almost always gets worse over time.

Are there any new drugs that might cause lung scarring?

Yes. Immune checkpoint inhibitors - drugs like Keytruda and Opdivo used for melanoma and lung cancer - are now the fastest-growing cause of DIPF. These drugs boost the immune system to fight cancer, but sometimes the immune system attacks the lungs instead. Doctors are still learning how to spot it early.

Can I switch to a different medication if I’m on one that causes lung damage?

Often, yes. For example, if you’re on methotrexate for arthritis and develop lung symptoms, your rheumatologist can switch you to sulfasalazine, leflunomide, or a biologic. For heart rhythm issues, alternatives to amiodarone include dronedarone or beta-blockers. Never stop a drug without medical supervision - but do ask about safer options.

Should I get a lung scan before starting a high-risk drug?

It’s a smart idea. A baseline chest CT and pulmonary function test (PFT) can help your doctor compare future changes. If you’re starting amiodarone, methotrexate, or long-term nitrofurantoin, ask for these tests. They’re non-invasive, quick, and can catch early signs of damage before you even feel symptoms.

If I stop the drug, will my lungs heal?

It depends. If caught early - within weeks or a few months of symptoms starting - most people see improvement. About 75-85% recover well. But if scarring is advanced, the damage is permanent. The lungs can’t regrow healthy tissue. That’s why timing matters more than anything.

Trevor Davis

January 13, 2026 AT 03:32Man, I never thought about this. My grandma was on nitrofurantoin for years for UTIs and just started coughing all the time. We thought it was just aging until she got diagnosed. Scary how quiet this stuff is.

Lethabo Phalafala

January 14, 2026 AT 05:59MY HEART IS BROKEN. I watched my sister go from hiking mountains to needing oxygen because they kept telling her it was "just allergies." She was on methotrexate for psoriasis. They didn't even ask about her breathing. 45 cases in New Zealand? That's 45 families shattered. This needs to be on every prescription label.

Lance Nickie

January 15, 2026 AT 00:49lol so amiodarone gives you lung cancer? nah its just fibrosis. same diff.

Milla Masliy

January 16, 2026 AT 12:47I’m from the US and my dad’s on amiodarone. We just got his PFT done last month-baseline was good. I’m gonna push for repeat tests every 6 months now. This post made me realize how little docs actually monitor this stuff. Thanks for the wake-up call.

Damario Brown

January 17, 2026 AT 16:52Here's the real issue: 78% of patients report dyspnea but only 58% of GPs screen for it. That's not negligence-that's systemic failure. We're medicating people into respiratory failure because we're too lazy to ask the right questions. And don't get me started on how pharma pushes these drugs without adequate post-market surveillance. This isn't an accident-it's a profit-driven oversight. Wake up, people.

Clay .Haeber

January 18, 2026 AT 00:43Oh wow, so taking a pill is now equivalent to signing a death warrant? Next you'll tell me aspirin gives you spontaneous combustion. I mean, sure, if you take amiodarone for 12 years and ignore every cough like a zombie, sure, maybe-but that’s not a drug problem. That’s a human problem. Also, "30 people died"? That’s less than the number of people who die from poorly made coffee in a year. Put it in perspective, please.

Priyanka Kumari

January 19, 2026 AT 03:46This is such an important post. I work in a clinic in India and we see patients on long-term nitrofurantoin all the time-no one asks about breathing. I’ve started adding a simple question to intake forms: "Have you noticed new shortness of breath or dry cough?" Just that one question has led to two early diagnoses. Small steps matter. Thank you for sharing the data-it gives us the courage to push for change.

Avneet Singh

January 20, 2026 AT 15:04While the clinical data is statistically significant, the rhetorical framing lacks nuance. The term "scarring" is emotionally loaded and conflates radiological findings with clinical outcomes. Moreover, the 8.2-week diagnostic delay metric is confounded by selection bias-patients presenting with symptoms are inherently more likely to be diagnosed. A more rigorous analysis would control for prescribing patterns and comorbidity burden. Also, why cite New Zealand? Their pharmacovigilance system is not representative of global populations.

Nelly Oruko

January 21, 2026 AT 02:14It’s strange how we trust chemicals we don’t understand… but fear the silence of our own bodies. We’ll take a pill for a headache, but ignore the whisper in our chest. Maybe the real drug isn’t the one in the bottle-it’s the belief that medicine always knows best. We’ve outsourced our intuition. And now, lungs are the price.