Generic Drug Classifications: Types and Categories Explained

Dec, 1 2025

Dec, 1 2025

When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see a simple name like metformin or lisinopril. But behind those names are complex systems that organize thousands of drugs into categories - systems doctors, pharmacists, and insurers rely on every day. These aren’t just labels. They determine how a drug is prescribed, covered by insurance, regulated by law, and even how it’s named. Understanding how generic drugs are classified helps you make smarter choices about your health and know why your doctor or pharmacist might suggest one version over another.

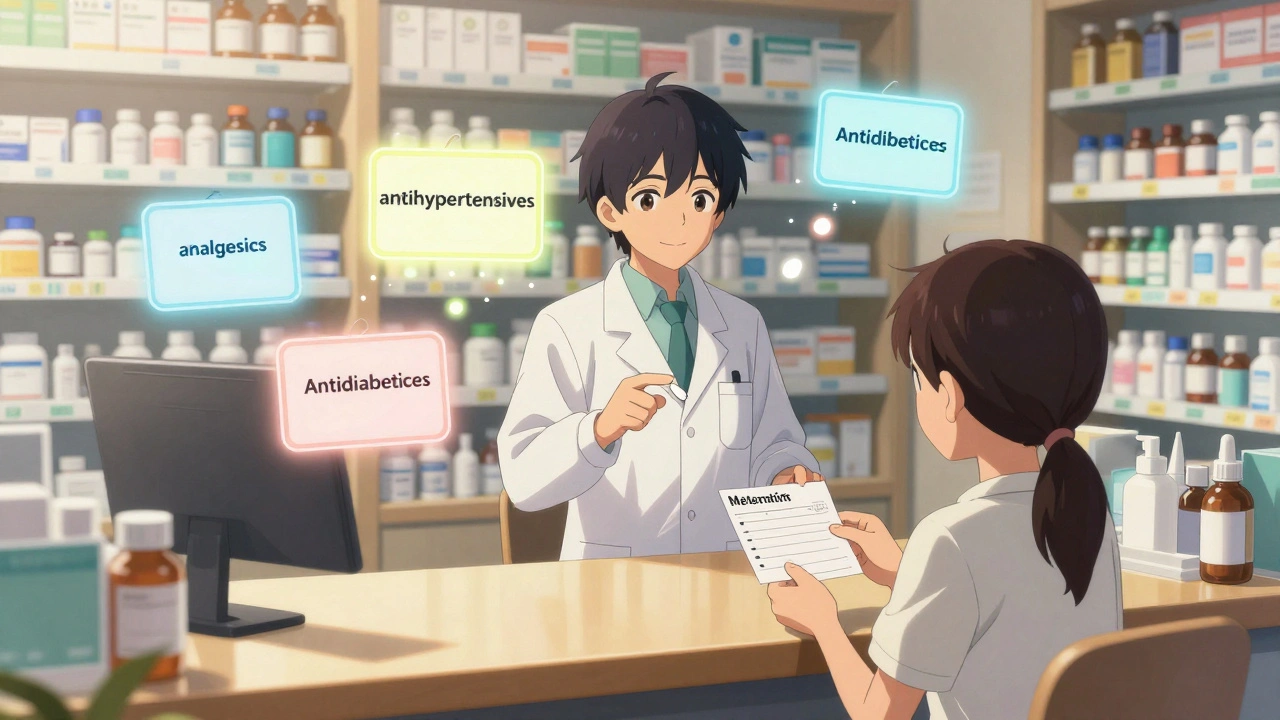

Therapeutic Classification: What the Drug Is Used For

This is the most common way drugs are grouped - by the medical condition they treat. Think of it as sorting medicines by their job. A painkiller goes in the analgesics category. A blood pressure med goes in cardiovascular agents. This system is used by 92% of U.S. hospitals, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), because it’s practical for doctors making daily decisions.

The FDA’s USP Therapeutic Categories Model breaks drugs into broad groups like:

- Analgesics - for pain relief (includes both non-opioids like ibuprofen and opioids like oxycodone)

- Antihypertensives - for lowering blood pressure (like lisinopril, amlodipine)

- Antidiabetics - for managing blood sugar (metformin, glimepiride)

- Antidepressants - for mood disorders (sertraline, fluoxetine)

- Antineoplastics - cancer treatments (paclitaxel, capecitabine)

Each of these has subcategories. For example, under analgesics, you’ll find NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and opioids. Under antihypertensives, you’ll find ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers. This structure helps doctors quickly find alternatives if one drug doesn’t work or causes side effects.

But it’s not perfect. Some drugs do more than one job. Aspirin, for example, reduces pain, prevents blood clots, and can lower inflammation. In a strict therapeutic system, it could belong in three categories. That’s why newer versions, like the FDA’s Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0 (coming in 2025), allow for primary and secondary uses. This change is critical as more drugs are developed to treat multiple conditions at once.

Pharmacological Classification: How the Drug Works

While therapeutic classification asks, “What does this drug treat?”, pharmacological classification asks, “How does it work?” This system dives into the biological mechanism - the exact molecular interaction that makes the drug effective.

For example:

- All drugs ending in -lol (like propranolol, metoprolol) are beta-blockers - they block adrenaline receptors to slow heart rate and lower blood pressure.

- All drugs ending in -prazole (like omeprazole, esomeprazole) are proton pump inhibitors - they shut down acid production in the stomach.

- Drugs like imatinib and erlotinib are kinase inhibitors - they block specific enzymes that cancer cells need to grow.

The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) recognizes 87 standardized drug name stems like these. They’re not random. They’re designed to tell you the drug’s class just by its name. This helps reduce errors - if you see a name ending in “-tidine,” you know it’s likely an H2 blocker for ulcers.

There are over 1,200 distinct pharmacological classes identified in medical literature. While this system is precise, it’s not always useful at the bedside. A patient doesn’t care that their pill is a “PDE5 inhibitor.” They care that it helps with erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. That’s why pharmacological classification is mostly used by researchers, pharmacists, and drug developers - not general practitioners.

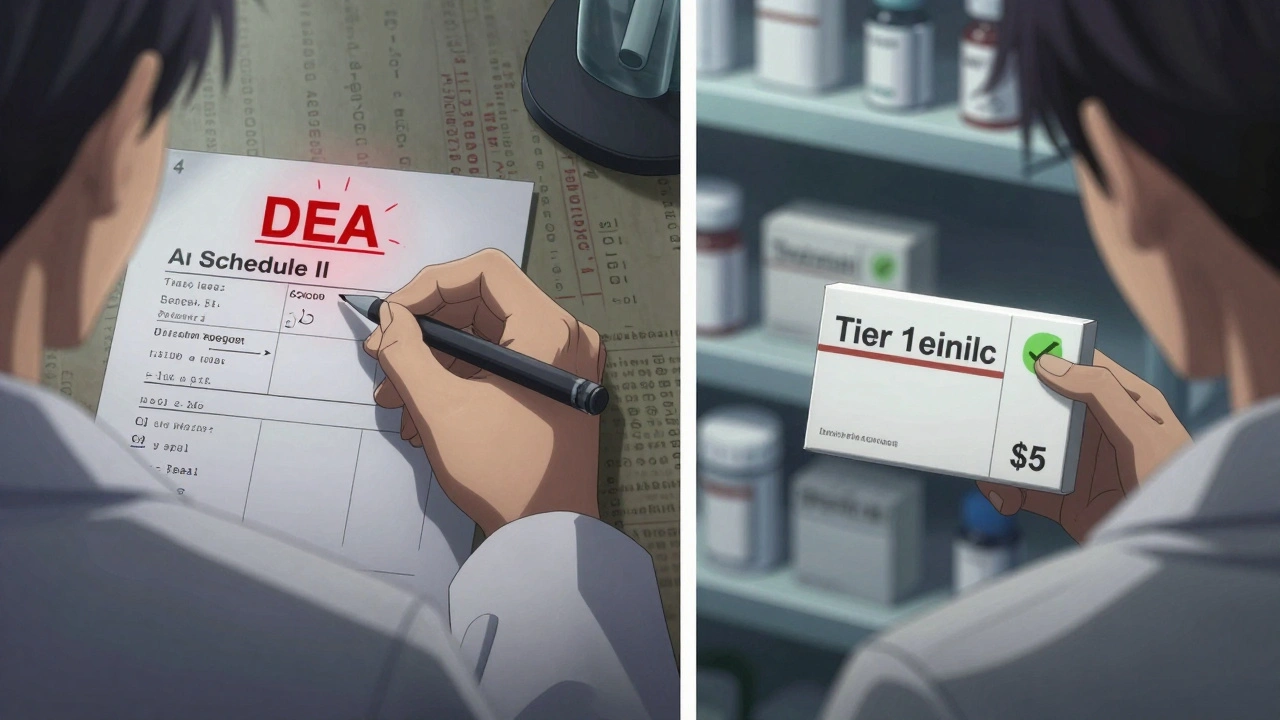

DEA Schedules: Legal Control and Abuse Risk

Not all drugs are treated the same under the law. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies controlled substances into five schedules based on their potential for abuse and accepted medical use. This system comes from the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 and affects prescribing rules, refill limits, and record-keeping.

Here’s how the schedules break down:

- Schedule I - No accepted medical use in the U.S., high abuse potential. Examples: heroin, LSD, marijuana (though this is changing).

- Schedule II - High abuse potential, but accepted medical use. Examples: oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall, methadone. No refills allowed.

- Schedule III - Moderate to low abuse potential. Examples: ketamine, buprenorphine, some combinations of codeine with acetaminophen. Up to 5 refills in 6 months.

- Schedule IV - Low abuse potential. Examples: benzodiazepines like alprazolam (Xanax), zolpidem (Ambien).

- Schedule V - Lowest abuse potential. Examples: cough syrups with less than 200mg codeine per 100ml.

This system is essential for pharmacies and prescribers to follow legal rules. But it’s also controversial. Marijuana is still Schedule I despite being approved for medical use in 38 states and having FDA-approved cannabinoid drugs like dronabinol (Schedule II). Critics say the system doesn’t reflect science - it reflects politics. The proposed MORE Act, if passed, could move marijuana to Schedule III, which would change how it’s prescribed, taxed, and researched.

Insurance Tiers: What You Pay Out of Pocket

Your insurance plan doesn’t care if a drug is an ACE inhibitor or a Schedule II controlled substance. It cares about cost. That’s why most plans use a tier system to manage expenses.

Humana and other major insurers typically use a 5-tier structure:

- Tier 1 - Preferred generics. Lowest cost. Usually $5-$10 for a 30-day supply. About 75% of generic drugs fall here.

- Tier 2 - Non-preferred generics. Slightly higher cost, maybe $15-$20. Often the same active ingredient as Tier 1, but not on the insurer’s preferred list.

- Tier 3 - Preferred brand-name drugs. Cost $30-$50. You pay more because the insurer negotiated a discount with the manufacturer.

- Tier 4 - Non-preferred brands. $60-$100. These are drugs with cheaper generic alternatives available.

- Tier 5 - Specialty drugs. $100-$1,000+. Usually for complex conditions like cancer, MS, or rheumatoid arthritis.

Here’s the catch: two identical generic drugs - same active ingredient, same dosage, same manufacturer - can be on different tiers based on which company made the deal with your insurer. That’s why a pharmacist might say, “We can switch you to this version for $5 less.” It’s not about safety or effectiveness. It’s about contracts.

Pharmacists report that 43% of prior authorization requests come from tier disputes. Patients often don’t realize they’re paying more for the same medicine. Always ask: “Is there a Tier 1 generic available?”

ATC Classification: The Global Standard

If you travel or work with international health data, you’ll run into the WHO’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) system. It’s used in 143 countries and is the closest thing we have to a universal drug classification.

The ATC system uses a five-level code:

- Level 1 - Anatomical main group (e.g., A = Alimentary tract and metabolism, C = Cardiovascular system)

- Level 2 - Therapeutic subgroup (e.g., A10 = Drugs used in diabetes)

- Level 3 - Pharmacological subgroup (e.g., A10B = Blood glucose lowering drugs, excluding insulins)

- Level 4 - Chemical subgroup (e.g., A10BA = Biguanides)

- Level 5 - Chemical substance (e.g., A10BA02 = Metformin)

This system is incredibly detailed. It’s used in global drug research, public health reporting, and insurance billing in Europe and Asia. In 2022 alone, 217 new ATC codes were added for new drugs. The WHO updates the system quarterly to keep up.

It’s not perfect. It doesn’t cover DEA schedules or insurance tiers. But for tracking drug use across countries - like how many people take statins or insulin - it’s unmatched.

Why Classification Confusion Costs Time and Money

Here’s the real problem: no single system tells the whole story. A doctor might think in therapeutic terms. A pharmacist checks DEA schedules for refill rules. A pharmacist checks insurance tiers for cost. A researcher uses ATC codes. And none of these systems talk to each other well.

According to a 2022 American Medical Association survey, 79% of primary care doctors spend 12 to 18 minutes per patient just sorting through conflicting classifications. Family doctors report even higher confusion rates - 23% more than specialists - because they deal with broader conditions and more medications.

Medication errors linked to classification confusion account for 27% of all reported incidents, per the FDA. One common mistake: prescribing a Schedule II drug with a refill without realizing it’s not allowed. Another: switching a patient to a “similar” generic that’s actually on a higher tier, leading to unexpected bills.

Health systems are trying to fix this. Electronic health records like Epic and Cerner now pull in multiple classification systems automatically. But setting them up takes 40-60 hours per hospital. And many providers still don’t use the official FDA or USP training materials. Only 38% of prescribers regularly consult them.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Drug classification isn’t frozen in time. New drugs are changing the rules.

By 2025, the FDA’s updated Therapeutic Categories Model 2.0 will require all new drugs to list primary and secondary uses. This matters for drugs like semaglutide (Wegovy), which treats both type 2 diabetes and obesity. Under old rules, it might’ve been lumped into just one category. Now, it can be recognized for both.

Biologic drugs - made from living cells, not chemicals - don’t fit traditional naming systems. A new drug for rheumatoid arthritis might have a name like “adalimumab” with no clear stem. The WHO’s 2024 ATC update will add 32 new codes just for these biologics and cell therapies.

Artificial intelligence is stepping in. IBM Watson Health’s Drug Insight platform, launched in 2023, uses machine learning to predict the best therapeutic category for a new compound with 92.7% accuracy. It’s still experimental, but it shows where the future is headed: smarter, data-driven classification that adapts as drugs evolve.

One thing is clear: as precision medicine grows - where treatments are tailored to your genes, lifestyle, and disease subtype - the old one-size-fits-all classification systems will struggle. Experts like Dr. Robert Temple at the FDA say future systems must integrate genetic data. Others warn we’re on the edge of fragmentation. Without a unified approach, confusion will only grow.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize all the categories. But you should know a few things:

- If your doctor prescribes a generic, ask if it’s a Tier 1 drug. You could save $10-$30 a month.

- If you’re on a controlled substance, know your schedule. Schedule II drugs can’t be refilled - plan ahead.

- Generic names ending in “-prazole,” “-lol,” or “-tidine” tell you the drug class. That’s useful if you’re comparing options.

- If you’re switching pharmacies or insurers, your drug might change tiers. Don’t assume the price stays the same.

- If you’re unsure why you’re taking a drug, ask your pharmacist: “What’s this for, and how does it work?”

Drug classification systems are meant to protect you - not confuse you. When they work right, they help you get the right medicine at the right price. When they don’t, they create delays, errors, and extra costs. Being informed helps you speak up and get better care.

What is the difference between therapeutic and pharmacological classification?

Therapeutic classification groups drugs by the medical condition they treat - like diabetes or high blood pressure. Pharmacological classification groups them by how they work at the molecular level - like blocking receptors or inhibiting enzymes. One tells you what the drug does for you; the other tells you how it does it.

Why are some generic drugs more expensive than others?

Even if two generic drugs have the same active ingredient, they can be on different insurance tiers. Tier 1 generics are preferred and cost the least. Tier 2 generics are the same drug but not on the insurer’s preferred list, so they cost more. It’s not about quality - it’s about which company made the best deal with your insurance plan.

Can a drug be in more than one DEA schedule?

No. Each drug is assigned to one DEA schedule based on its abuse potential and medical use. But a single drug can have multiple formulations - for example, a low-dose codeine cough syrup might be Schedule V, while a higher-dose tablet is Schedule III. Each formulation gets its own schedule.

How do I know if my drug is a generic?

Look at the name on the label. If it’s a chemical name like “metformin” or “amlodipine,” it’s a generic. Brand names are capitalized and trademarked, like Glucophage or Norvasc. Generics are always cheaper and contain the same active ingredient as the brand.

Is the ATC system used in the United States?

The U.S. doesn’t use ATC as its main system, but many research institutions, hospitals, and insurers use it for data tracking and international reporting. The FDA and USP systems are used for prescribing and regulation, while ATC helps compare drug use across countries.

Will marijuana’s classification change soon?

As of late 2023, marijuana remains a Schedule I drug under federal law, despite being legal for medical use in 38 states. The MORE Act, passed by the House in 2023, would move it to Schedule III, but it’s stalled in the Senate. If it passes, it would change how doctors prescribe it, how taxes are applied, and how research is funded.

Jaswinder Singh

December 3, 2025 AT 09:16Bro this post is a goddamn textbook chapter. I read half of it on my phone while waiting for my prescription and nearly cried from info overload. Who the hell writes this much? But honestly? Kinda amazing.

Eric Vlach

December 3, 2025 AT 17:59Really appreciate the breakdown on tiers. I had no idea two identical generics could cost different amounts just because of insurance deals. My pharmacist switched me last month and I saved $22. Just ask for Tier 1. Seriously. Do it.

Bee Floyd

December 5, 2025 AT 10:42Love how you tied in the real-world messiness - doctors juggling 5 systems at once, pharmacists playing translator, patients getting hit with surprise bills. It’s not about the science, it’s about the system being a Rube Goldberg machine made of spreadsheets and contracts. 🤷♂️

ANN JACOBS

December 5, 2025 AT 18:52As someone who has spent over two decades working in health informatics, I must commend the thoroughness of this exposition. The integration of therapeutic, pharmacological, DEA, insurance tier, and ATC classification systems represents a remarkable, albeit fragmented, achievement in medical taxonomy. The fact that these systems were developed independently across disparate domains - clinical practice, regulatory policy, economic modeling, and global public health - speaks to the complexity of pharmaceutical governance in a pluralistic society. It is not merely a matter of nomenclature; it is a reflection of institutional inertia, competing epistemologies, and the inherent tension between standardization and adaptability. The emergence of AI-driven classification platforms, such as IBM Watson Health’s Drug Insight, signals a paradigmatic shift toward dynamic, data-informed ontologies. However, without interoperable infrastructure and mandatory clinician training, even the most elegant algorithm will fail to mitigate the human cost of misclassification. I urge policymakers to prioritize unified classification frameworks in the next iteration of the National Health Information Network. The time for siloed thinking is over.

Priyam Tomar

December 7, 2025 AT 16:10Ugh. You say ATC is global but then admit the US doesn’t use it? That’s like saying ‘we have a universal language called English’ but then say Americans speak ‘American’. You’re just sugarcoating the fact that the US ignores global standards because it thinks it’s above them. Pathetic.

Irving Steinberg

December 7, 2025 AT 21:22Wow so many words for something that’s basically ‘ask your pharmacist if it’s the cheap one’ 😴 I just want my pills to not break my bank. Why does this feel like a college essay?

Shashank Vira

December 8, 2025 AT 23:32Let me be the first to point out the glaring omission: no mention of the pharmaceutical industry’s deliberate obfuscation of classification systems to maintain patent monopolies. The entire tier system? A manufactured illusion of choice. The DEA schedules? A political theater masking corporate lobbying. The ATC system? A tool for global data extraction by Big Pharma. This post reads like a whitepaper funded by a pharmacy benefit manager. The truth? The system is designed to confuse you so you don’t ask why your $5 generic is suddenly $47.

Jack Arscott

December 10, 2025 AT 15:15THIS. I had no idea the ‘-prazole’ ending meant anything 😮💨 Now I look at my meds like a code. Omeprazole = acid stopper. Metoprolol = heart chill pill. So cool. Thanks for this 🙌

Souvik Datta

December 11, 2025 AT 02:56Keep going. This is the kind of clarity we need. Too many people think ‘generic’ means ‘weaker’ - but it’s just cheaper because the patent expired. You’re not just learning drug names - you’re learning how to navigate a broken system with your eyes wide open. Stay curious. Stay empowered.

Courtney Co

December 11, 2025 AT 03:46Okay but what if you’re on Medicaid and your Tier 1 generic isn’t covered because your state only approves the one from the company that lobbied the most? I had to wait 3 weeks for a prior auth just to get my blood pressure med and my kid missed school because I was in the pharmacy arguing with a robot. This isn’t information - it’s trauma with footnotes.

Jeremy Butler

December 11, 2025 AT 06:36The fundamental inadequacy of contemporary pharmaceutical taxonomy lies in its failure to reconcile ontological plurality with epistemic unity. Therapeutic classification is teleological; pharmacological, mechanistic; DEA, juridical; insurance, economic; ATC, taxonomic. These are not merely divergent systems - they are incompatible paradigms. The emergence of AI-driven classification, while technologically impressive, merely automates the epistemic chaos rather than resolving it. The patient, caught in the interstices of these systems, becomes not a subject of care, but a node in a bureaucratic lattice. Until we construct a unified, patient-centered ontological framework - one that integrates biological, legal, economic, and phenomenological dimensions - we are not treating disease, but managing classification error.